Processed Food Addiction: Foundations, Assessment, and Recovery is NOT a beach read. That is unless you have insomnia on vacation. Joan Ifland, Marianne Marcus, and Harry Pruess have delivered a serious tome on the dangers of processed food. It is not a pretty sight. I waded through 31 chapters and 454 pages in my quest to understand the subject. It is a technical book written in strict, academic form. The book represents a major advance in the field since Food and Addiction. What a remarkable achievement in just a few years. The field has attracted many researchers. Over the next three weeks I will present their findings, the case they make, and my assessment of that case. For a nontechnical summary of the key points in the book see a popular article by the senior editor.

Processed Food Addiction: Foundations, Assessment, and Recovery is NOT a beach read. That is unless you have insomnia on vacation. Joan Ifland, Marianne Marcus, and Harry Pruess have delivered a serious tome on the dangers of processed food. It is not a pretty sight. I waded through 31 chapters and 454 pages in my quest to understand the subject. It is a technical book written in strict, academic form. The book represents a major advance in the field since Food and Addiction. What a remarkable achievement in just a few years. The field has attracted many researchers. Over the next three weeks I will present their findings, the case they make, and my assessment of that case. For a nontechnical summary of the key points in the book see a popular article by the senior editor.

Substance abuse not process abuse. The thrust of Processed Food Addiction hinges on the difference between substance abuse and process abuse. DSM 5 differentiates between the two disorders. The book labels food addition as a Substance Use Disorder (SUD). Examples of substances causing SUDs are alcohol, hallucinogens, marijuana, nicotine, opiods, sedatives, and stimulants. We would classify eating addiction is a Process Use Disorder (PUD). PUDs include gambling, shopping, sex, and video game addictions. The rationale given is that “addictive substances must be misused in the behavior” (11). I understand that all current SUDs trace back to a single chemical. Declaring food abuse as an SUD would be a departure from that practice. Or would it?

References

(1) Ifland, J., M.T. Marcus, and H.G. Preuss, 2018. Introduction: Learning about processed food addiction. Processed Food Addiction xiii-xvii.

(2) Ellis, R.J., M. Michaelidis, and G-J. Wang, 2018. Neurodysfunction in addiction and overeating as assessed by brain imaging. Processed Food Addiction 27-38.

(3) Ifland, J. and P.M. Peeke, 2018. Overlap between drug and processed food addiction. Processed Food Addiction 3-25.

(4) Stice, E. and Z. Stice, 2018. Neural vulnerability factors for overeating: Treatment implications. Processed Food Addiction 39-55.

(5) Marcus, M.T., 2021. Mindfulness therapies for food addiction. Processed Food Addiction 107-118.

(6) Ifland, J. and E. Epstein, 2018. DSM 5 SUD criterion 3: Time spent. Processed Food Addiction 175-186.

(7) Ifland, J. and C.L Willie, 2018. DSM 5 SUD criterion 5: Failure to fulfill roles. Processed Food Addiction 205-215.

(8) Ifland, J. 2018. Adaptation of SUD and ED practice parameters to adolescents and children with PFA. Processed Food Addiction 397-416.

(9) Ifland, J., K.K. Sheppard and H.T. Wright, 2018. The Addiction Severity Index in the assessment of processed food addiction. Processed Food Addiction 289-303.

(10) Criscitelli and N.M. Avena, 2018. Sugar and fat addiction. Processed Food Addiction 67-75.

(11) Ifland, J., H.G. Pruess, M.T. Marcus, W.C. Taylor, K.M. Rourke, H.T. Wright, K.K. Sheppard, 2018. Abstinent food plans for processed food addiction. Processed Food Addiction 77-106.

(12) Pruess, H.G. and J. Ifland, 2018. Sugar consumption: An important example whereby recognizing food addiction may prove important in gaining optimal health. Processed Food Addiction 57-66.

(13) Ahmed, S.H., 2012. Is sugar as addictive as cocaine? Food and Addiction 231-237.

(14) Ifland, J. 2018. DSM 5 SUD criterion 4: Cravings. Processed Food Addiction 187-204.

(15) Zeidonis, D.M. and J. Ifland, 2018. Premises of recovery for adults. Processed Food Addiction 321-340. Chapter 24

(16) Ziedonis, D.M. and J. Ifland, 2018. Avenues of success for the practitioner. Processed Food Addiction 341-353. Chapter 25

(17) Ifland, J., 2018. Strategies for helping food-addicted children. Processed Food Addiction 417-447.

(18) Gold, D., 2018. Case study: Severe processed food addiction. Processed Food Addiction 147-155.

(19) Willey, C.L. and J. Ifland, 2018. Adaption of APA practice guidelines for SUD to processed food addiction. Processed Food Addiction 355-374.

(20) Meule, A., 2018. Assessment of food cravings. Processed Food Addiction 137-145.

(21) Ifland, J. and H.T. Wright, 2018.DSM 5 SUD criterion 11: Withdrawal. Processed Food Addiction 277-287.

(22) Donovan, D.M. and J. Ifland, 2018, Diagnosing and assessing processed food addiction. Processed Food Addiction 121-136.

(23) Ifland, J. and D.M. Ziedonis, 2018. Introduction to recovery from processed food addiction. Processed Food Addiction 207-320.

(24) Ifland, J. and J.M. Cross, 2018. DSM 5 SUD criterion 8: Hazardous use. Processed Food Addiction 241-254.

(25) Ifland, J. and C.L. Willey, 2018. DSM 5 SUD criterion 10—tolerance. Processed Food Addiction 263-276.

(26) Ifland, J. and H.T. Wright, 2018. Insights from the field. Processed Food Addiction 383-396.

(27) Ifland, J., H.G. Pruess, and M.T. Marcus, 2018. Conclusion: Nurturing the sapling. Processed Food Addiction 449-454.

(28) Ifland, J. and R. Piper, 2018. Preparing adults for recovery. Processed Food Addiction 375-381.

(29) Ifland, J. and R.S. Roselle, 2018. DSM 5 SUD criterion 9: Use in spite of consequences. Processed Food Addiction 255-262.

(30) Penzenstadler, L., C. Soares, L. Karila, and Y. Khazaal, 2019. Systematic review of food addiction as measured with the Yale food addiction scale: Implications for the food addiction construct. Current Neuropharmacology17(6):526-538. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30406740/

(31) Stein, D., S. Deberard, and K. Homan, 2013. Predicting success and failure in juvenile drug treatment court: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 44(2):159-168.

(32) Smiley, R. and K. Reneau, 2020. Outcomes of Substance Use Disorder monitoring programs for nurses. Journal of Nursing Regulation 11(2):28-35. https://www.ncsbn.org/OutcomesofSubstanceUseDisorderMonitoringProgramsforNursesJNR.pdf

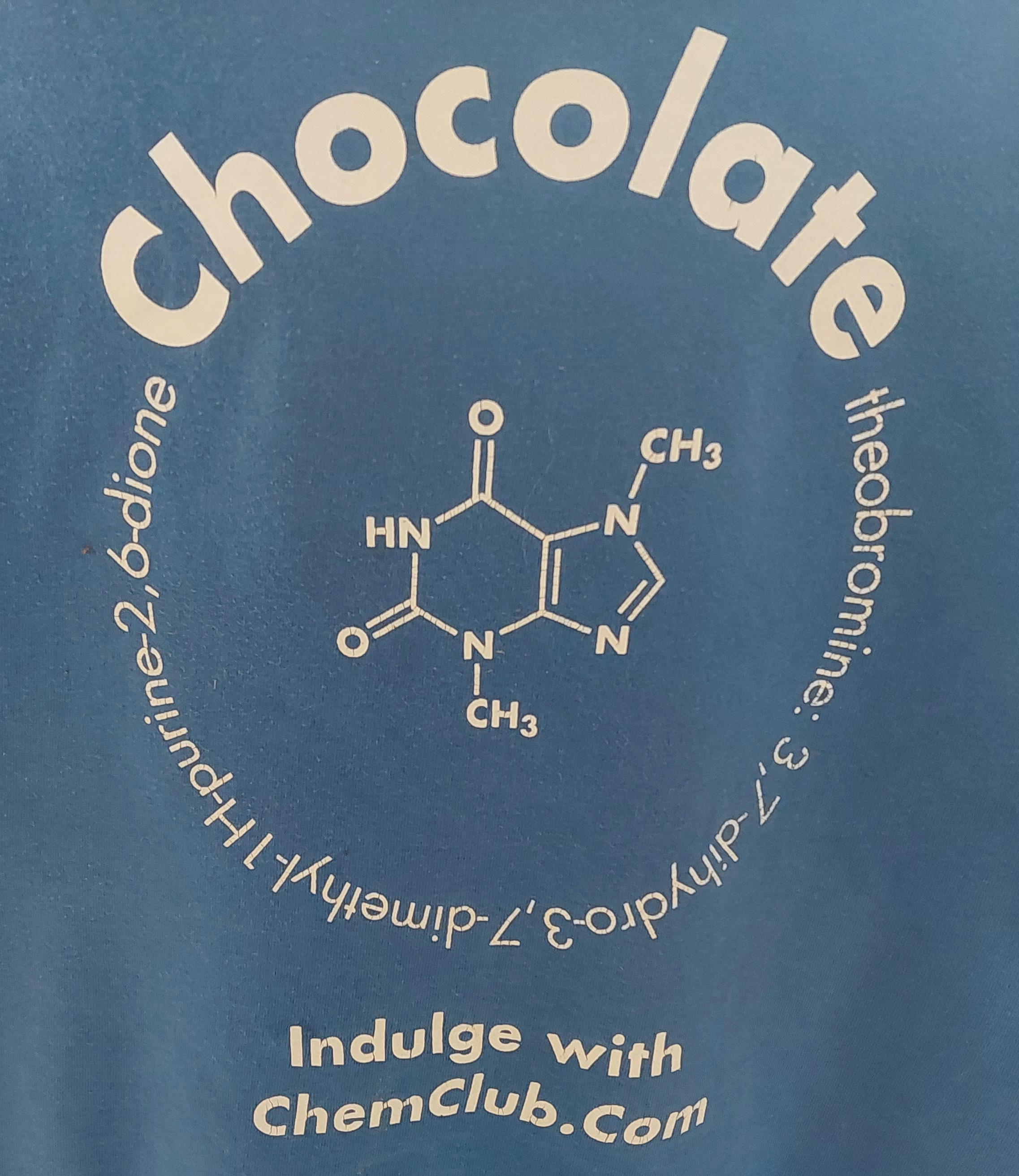

Thank you for your comments and formulas. No bromine in theobromine? Like no chlorine in chlorophyll, which annoys the chlorophobes.

Number of additive substances (15,000) is irrelevant and worse yet, misleading. How much matters, “dose makes the poison”(Paracelsus). Why are people so resistant (scared?) to see this?

I’ll await next week to see if they cover nonbiological reasons for eating, including the comfort aspect of infant nursing, which may relate to addiction.

LikeLike

Their biggest hole in the food addiction theory is there is no substance in the Substance Use Disorder. All other SUDs link directly to a chemical. They don’t even understand chemicals much less the dose makes the poison. You will be disappointed about the nonbiological reasons. Infant nursing is addressed.

LikeLike