What does the FDA require on a food label?

What are the FDA’s goals in setting the requirements?

How effective are FDA’s efforts?

The answers to these questions are not as simple as they may seem. And the answers keep changing as the FDA tries to keep up with its critics and a changing society.

For a food company, a product label seeks to grab the attention of potential customers and remind loyal ones that it is still around. Graphics draw people in to help make a sale. The FDA sides with the consumer requiring certain information on each label to help the buyer make that decision.

A packaged food label must include the common name of the food, its net weight, the ingredients statement, and the Nutrition Facts statement.* All labels on a packaged food product must also warn the consumer of the presence of any dangerous allergens.

* a brief note of explanation. The link shown above was generated by AI through Bing. I am not a big AI guy, but the link is the best, brief description I could find on the requirements for a food label.

A recent book, From Label to Table, helps us better understand the label in its current form, how it has changed over the decades, and FDA’s evolving perspective on how best to keep the consumer from falling victim to possible deception. To perform its mission, the FDA must identify and define its target consumer. At that point the agency develops a strategy to either protect, inform, or nudge consumers to maintain or improve their collective health and well-being. In the meantime FDA finds itself caught in the middle of what Linn Steward calls the battle of Big Food against Big Public Health.

Transition from scarcity to abundance. As America emerged from World War II, it became a nation governed more by abundance than scarcity, at least for the growing middle class. Packaged food products claimed a greater portion of the American food supply. The prevailing sentiment changed from “let the buyer beware” to expecting the government to become a “guarantor of the public’s trust.” The FDA and related agencies had relied on standards of identity or defined sets of ingredients for common processed foods like ice cream, ketchup, and mayonnaise. Such standards were becoming outdated with changes in food manufacture and modern society. The FDA fought against 4 common nutritional myths:

-

- poor diets were responsible for all diseases,

- soil depletion leads to losses of nutrients in foods,

- nutritional value a food is degraded by food processing, and

- subclinical deficiencies in nutrients result in subclinical nutritional diseases.

To be on the side of the consumer, the agency needed to imagine the traits of a typical consumer and anticipate wants and needs. Again, not an easy task!

Protecting the “ordinary consumer” became the mission of the FDA in the 1950s and 60s. Diseases of affluence emerged in addition to diseases of hunger. Big Food was blamed for causing both chronic illness and hunger. Food stamps became the answer for preventing hunger. Food pantries entered the picture to administer emergency food relief. With regard to more nutritious foods, differences of opinion on the best way to solve the problem became apparent between consumer interests and expert interests. Consumer advocacy had arrived and governmental interference was not welcomed. The 1969 White House Conference on Food, Nutrition, and Health addressed many of the issues associated with consumerism and processed foods.

In its mission of protecting the consumer the agency was trapped between vocal criticisms from consumer advocates and resistance to change by the food industry. Experts ranging from toxicologists, nutritionists, dietitians, and food scientists tend to side with the industry and against the advocates. Nowhere was there more tension between advocates and experts as on the issue of “chemical additives.”

Protecting the consumer from diseases of affluence and hunger was not working. Was the FDA reaching the right consumer? Did the consumer need more useful information?

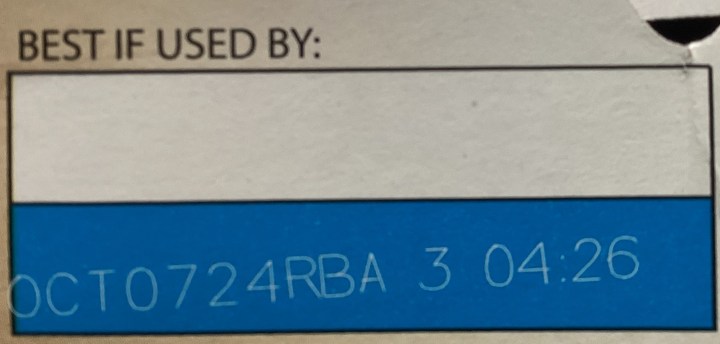

Providing the “informed consumer” with ingredient statements and nutritional labels refocused the FDA’s approach to the consumer. Pushed by anti-government activism on the left and the right, the agency retooled the label of packaged foods. Expiration dates, although not a requirement, started popping up on labels such as Best Used Before . . . dates. Perhaps no information on food labels is more misunderstood than expiration dates. Manufacturers provide these dates to encourage consumers to eat the product before off flavors, colors, or textures develop in the food. Consumers associate detectable changes in a product or one that is past the date on the package as an indication of an unsafe food. A spoiled food can be safe to eat. An unsafe food can be perfectly acceptable in flavor, color, and texture. Sniffing is a good at detecting spoilage but not good at detecting safety hazards.

Consumer advocates like Ralph Nader and James Turner challenged the regulatory principles of government experts. Strong opposition to “chemical additives” by advocates countered support by toxicologists and other so-called experts. “Chemical additives” were reviewed, but, for the most part, stayed in products. Such additives need to appear in the label’s Ingredient Statement. Primary ingredients are listed on the label followed by sub-ingredients listed in parentheses following each primary ingredient. The common name of each primary ingredient is required to be on the label. Rather than illuminating the chemical composition of a food product, these statements foster a perception that processed foods are complex combinations of numerous chemicals and that whole foods are chemical free.

Nutritional labeling was another attempt at informing the consumer. Based on the assumption that providing the consumer with knowledge on the nutrients present in a product would help in proper selection led to the birth of the Nutrition Facts. The statement also includes information on fat, salt, and sugar present. The idea was that informed consumers would choose products for a balance of foods containing more “good” nutrients and less “bad” components. Big Food of course emphasized the abundance of “good” nutrients and Big Public Health pointed to presence of too much of the “bad” components. Big Food became particularly effective at designing foods to provide the best Nutrition Facts profile.

Certain consumer activists coined the term nutritionism to condemn an overemphasis on nutritional composition. Food companies developed a series of functional foods designed to meet a specific nutritional profile or meet a specific nutritional need. Product developers in the industry tailored their formulations to gain maximum benefit from the label. Many consumers flocked to dietary supplements leading to overreliance on selected vitamins and minerals.

Consumer activists were generally positive about changes to the labels and the food industry generally negative. After product developers and marketers learned how to use the label changes, particularly the Nutrition Facts, to their advantage consumer advocates were less pleased. It became clear that that providing information to inform the consumer was not working either. The agency gave up trying to understand the consumer, suggesting a new strategy.

Nudging the “rationally irrational consumer” to do the right thing. It seems like the consumer is not always rational, but may be influenced to be more socially responsible. By aligning healthy eating practices with goals such as sustainability without overt linkage, would many consumers fall in line? The recent White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health of 2022 led to a document that challenges the nation to find solutions. The FDA has developed a formula to define the term “healthy” on a processed food product.

Will the new strategy work to create more healthy foods and more healthy consumers? Probably not! The vicious cycle could continue. FDA makes a major change in the food label. Big Public Health supports the change. Big Food resists the initiative until it finds ways to “game the system” and produce healthy ultraprocessed food products. Just like the terms authentic, transparent, and clean label before it, healthy will become a battlefield. The more FDA tries to define healthy, the more palatability will be sacrificed as the less fat, salt, and sugar will be allowed. Enter more alternative ingredients to produce tasty, healthy alternatives.

FDA is fighting a losing cause. The deck is stacked against it. The agency targets a broad slice of consumers while ignoring the rest. A food company can define a specific consumer target for each individual product. The more quantitative measures for selected ingredients the agency develops to define common concepts, the more innovative food product designers will become. Two sets of products will emerge: (1) those that entice the consumer to more hedonistic pleasure without ingredient restrictions, and (2) healthy versions for meeting the FDA guidelines for sugar, fat, and salt. Journalists and consumer activists will cry foul, wringing their hands as the percentage of ultraprocessed calories consumed by Americans increases, demanding another response from the agency.

Seeking out the “reasonable consumer” may be the an answer. The war between Big Public Health and Big Food is being fought in the court system. A recent case over smiling packages of Hershey’s Peanut Butter Cups may be important in developing a standard. There are solutions to developing processed and ultraprocessed products that are healthier and tasty. But Big Food and Big Public Health and FDA will need to sit down at the table and act rationally. All parties will need to compromise, but solutions can be found. Only the “reasonable consumer” will benefit. As long as quantitative measures are used to define healthiness, the food industry will have the upper hand. As long as healthy means squeezing out tasty, consumers will continue to seek out tasty products, and consumer activists will have their issue to fight.

Coming soon: Aspartame and other chemicals in my food

* The link was generated by AI through Bing. I am not a big AI guy, but the link is the best, brief description I could find on the requirements for a food label.

4 thoughts on “What can we learn from a food label?”